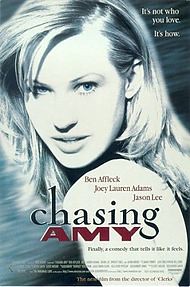

When I was 11, I saw the trailer for Chasing Amy. I don't remember why it caught my attention—I didn't recognize the actors, and I don't think I consciously knew what it was about. It certainly wasn't targeted toward 11-year-olds, so I'm not even sure where I saw the ad. But something in my gut told me that this was a movie I needed to see. It was the first time I experienced such a strong, immediate response to a movie, let alone a trailer.

When I was 11, I saw the trailer for Chasing Amy. I don't remember why it caught my attention—I didn't recognize the actors, and I don't think I consciously knew what it was about. It certainly wasn't targeted toward 11-year-olds, so I'm not even sure where I saw the ad. But something in my gut told me that this was a movie I needed to see. It was the first time I experienced such a strong, immediate response to a movie, let alone a trailer.

Of course, I'd have to wait awhile. My parents, always acting sensibly, didn't let me see it in theatres. (In hindsight, I can't blame them.) But a couple years later, once my parents let me walk to the video store and rent movies on my own, I watched Chasing Amy on VHS. I loved it. It was the funniest movie I'd ever seen, and I quickly decided that Kevin Smith had usurped Steven Spielberg's place in my heart and become my favorite director. More than anything, though, the film made me think. I had known gay people throughout my life and I understood what homosexuality meant, but until I saw Chasing Amy, it hadn't occurred to me that some people could be attracted to more than one gender. This realization suddenly made me start to understand certain feelings I had experienced since the sixth grade. Within a year of seeing the film, I became friends with a girl my age who identified as bisexual, I started high school, and I joined the Gay-Straight Alliance. The more involved I became in the LGBT community, the more I recognized my own attraction to women. In the summer of 2001, when I was 15, I came out to my friends and family as bisexual.

Here's the big problem I have with Chasing Amy: the word "bisexual" is never used. For those who haven't seen it, the basic plot is: boy meets girl, boy finds out girl is a lesbian, boy propositions girl anyway, girl surprises him by saying yes, girl loses her gay friends, boy starts acting like a jerk, girl dumps boy and starts exclusively dating women again. (Not the most romantic movie, is it?) What's interesting about Alyssa ("girl") is that she's open to experiencing sexuality and finding love in any number of ways. She has a history with men, but because she primarily enjoys sex and relationships with women, she claims the term "gay." When she decides to start a relationship with Holden ("boy"), she tells him it's because she doesn't want to "limit the likelihood of finding that one person who'd complement me so completely." But at no point does she change her identification. From start to finish, Alyssa identifies as a lesbian, and because of this, the viewer expects her relationship with Holden to fail.

Alyssa's self-identification and character arc perplexed me, but it also reinforced a reality I experienced constantly throughout high school. Most people around me weren't as psyched as I was about my newfound bisexuality. It wasn't that they were homophobic—they weren't. They just didn't understand how I was able to like more than one gender. I was told I was confused. I was told I had to pick a side. I was told it was a phase. And because these messages bombarded me in life and in the media, I let them sink in. So when I was 17, I picked a side. Knowing that I fall closer to the 6 than the 0 on the Kinsey Scale, I came out as a lesbian. It wasn't an arbitrary or even a conscious decision. It just felt like the option available to me.

You already know the end of the story: I'm back to identifying as bisexual. Once I fell in love with Anders, the man who's now my husband, I started giving serious thought to these labels we have and what they mean. In an attempt to better understand my feelings, I gave Chasing Amy another viewing. I thought again about Alyssa's explanation for dating Holden, "to not limit the likelihood of finding that one person who'd complement me so completely." It finally occurred to me that, while Chasing Amy doesn't actually talk about bisexuality, it promotes the message that you won't find what you want until you open yourself up to unexpected possibilities. And that's been true for me.

You already know the end of the story: I'm back to identifying as bisexual. Once I fell in love with Anders, the man who's now my husband, I started giving serious thought to these labels we have and what they mean. In an attempt to better understand my feelings, I gave Chasing Amy another viewing. I thought again about Alyssa's explanation for dating Holden, "to not limit the likelihood of finding that one person who'd complement me so completely." It finally occurred to me that, while Chasing Amy doesn't actually talk about bisexuality, it promotes the message that you won't find what you want until you open yourself up to unexpected possibilities. And that's been true for me.

Chasing Amy is a complicated text. Other than Alyssa, none of the characters are especially sympathetic. They compete with one another to make sure she chooses the "right" team. No one seems all that interested in her desires and intentions. Even Holden, who purports to be the person who loves Alyssa most, laments that they'll never be "a normal couple." This could be a commentary on biphobia, but because bisexuality isn't named or addressed directly, I doubt that it is. I think the more likely explanation is that Kevin Smith doesn't understand queer identity politics as well as he thinks he does. But in one scene, the scene when Alyssa is allowed a moment to speak and explain why she's dating Holden—"to not limit the likelihood of finding that one person who'd complement me so completely"—we get a completely candid and refreshing take on non-monosexuality. That scene makes the rest of the film, problematic though it may be, worth watching.

I'm telling you this story because it summarizes the reason I wanted to write about this topic for Bitch in the first place. The media—and our relationship to it—is complicated. A work can simultaneously validate our lived experiences and force us to conform to specific norms. This complexity is particularly apparent in depictions of bisexual and other non-monosexual people, but because media watchdog organizations like GLAAD don't prioritize bi issues the way they prioritize other queer issues, these flawed depictions often go unchecked. All we can do is recognize the positive elements and document the flaws, so that we can move toward better, more honest, and more affirming portrayals of bisexuality. If there's anything I've conveyed throughout this series, I hope that's it.

Related:The B Word: Chasing Amy and the Bisexual (In)Visibility in Cinema and Media, Chasing Amy

Previously:Toward a Visible Movement, Is Social Media the Final Visi(bi)lity Frontier?